Horological Machine N°11

Architect

It could be said that an MB&F Machine is not worn; it is lived. With its latest creation, MB&F further blurs the line between watchmaking and architecture.

The house that Max built

A watch and a house are different machines.

But the Machines of MB&F are habitable; the stories they tell locate us in different places or different times, and sometimes different worlds.

What's so special about this machine?

A rotating case, a flying tourbillon and a see-through sapphire crown are just three highlights from the HM11's unique features.

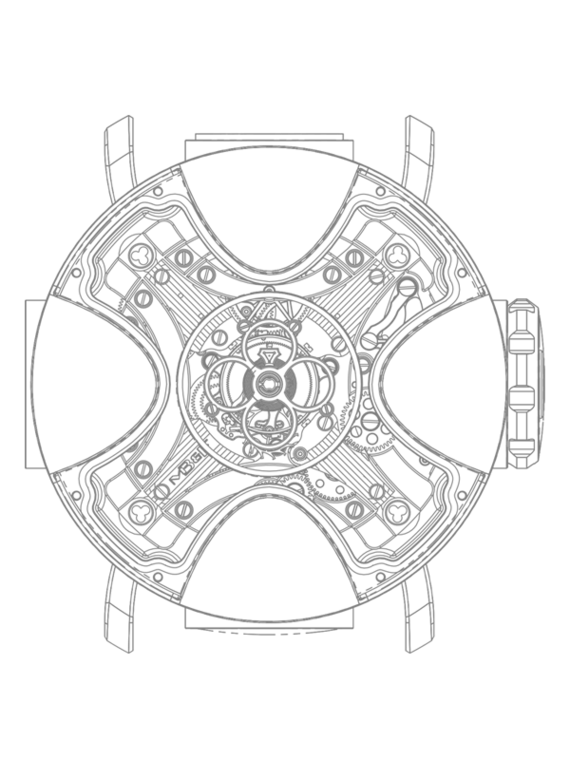

A CENTRAL FLYING TOURBILLON

A central flying tourbillon forms the heart of the house, pushing skyward under a double-domed sapphire roof. Fittingly, for a mechanism that is spatially and functionally at the origin point of the watch, its quatrefoil-shaped upper bridge recalls the shape of clerestory windows in some of humanity’s greatest temples to its Creator, or perhaps the shape of a zygote undergoing cell division at the moment of conception. From this spinning core, four symmetrical volumes reach outwards, creating the four parabolic rooms of the house that is HM11 Architect.

A ROTATING CASE TO DISPLAY FUNCTIONS & WIND THE MOVEMENT

Turn the house to access each room; the entire structure rotates on its foundations, simultaneously winding the movement. The 90° angle of offset between each room means that you can position HM11 with one of its rooms directly facing you, or with one of the corridors of the house running towards you and rooms obliquely to each side.

A SEE-THROUGH SAPPHIRE CROWN

An unprecedented feature in watchmaking is the see-through crown, close to 10mm in diameter, that allows an unimpeded view directly into the movement. A crown of this size in sapphire crystal, whilst undeniable in its aesthetic impact, comes with specific technical challenges to be overcome. As the primary point of ingress to the movement, a watch crown must be equipped with gaskets that prevent water or dust particles from entering the watch and compromising its performance.

At the heart of the engine are two words: Power & Efficiency

What if a house was a watch?

A central atrium that gives onto four peripheral rooms. Transparency and light. Interior volumes that interact with exterior perspectives, HM11 combines the beauty of architecture with watchmaking mastery.

- Two editions: In grade 5 titanium and blue dial plate limited to 25 pieces or grade 5 titanium and red gold dial plate limited to 25 pieces.

- Dimensions: 42mm (diameter) x 23mm (height)

- Number of components: 92

- Three-dimensional horological engine featuring bevel gears, composed of a flying tourbillon, hours and minutes, a power reserve indicator and temperature measurement, developed in-house by MB&F.

- Mechanical movement, manual winding (by turning the entire case clockwise)

- Power reserve: 96 hours

- Balance frequency: 18’000bph/2.5Hz

- Number of movement components: 364 components

- Number of jewels: 29 jewels

- Sapphire crystals on top, back, and on each chamber-display treated with anti-reflective coating on both faces

- Sapphire crown

- Hour and minutes

- Power reserve

- Temperature (-20 to 60° Celsius, or 0 to 140° Fahrenheit)

Inspiration

Somewhere around the mid- to late 1960s, architecture entered an experimental phase, starkly different from the designs of the previous decade.

Post-war buildings were pragmatic, rectilinear forms, hastily erected to fulfil a purpose. But then a small yet reactive movement began taking hold, one that was surprisingly humanistic in its approach, though not in a way that architectural scholars would use the term.

It was humanist in the sense that it moulded space around the form of a human body, the spherical scope of vision perceived by the human eye, the radial ambit of human limbs moving through the air, the roundness of the breath that inflates our lungs and creates ephemeral vapour halos on car windows in winter.

These architects, some of whom eschewed that title and instead called themselves habitologists, built houses which appeared as if they had been exhaled out of the earth, or as if the land had flexed its fingers and forgotten to curl them fully back up again. They bubbled, they undulated, they arched like an extended sinew. And when Maximilian Büsser, founder of MB&F, looked at one of these houses, he thought, “What if that house was a watch?”